When Thinness Becomes a Personality

Why the system still revolves around one kind of body: on runways, in offices, and online

From runway shows to digital lookbooks, thinness remains the dominant language of fashion. Even when it’s not explicitly stated, it’s present in the sizing of samples, the angles of editorials, and the types of bodies that get celebrated, or simply just ‘shown’. The recent news about Zara’s ads being banned by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority for showing “unhealthily thin” models isn’t surprising at all. What’s surprising is that we still pretend this kind of representation is an isolated mistake, when in fact it’s part of the design of the entire system we keep praising.

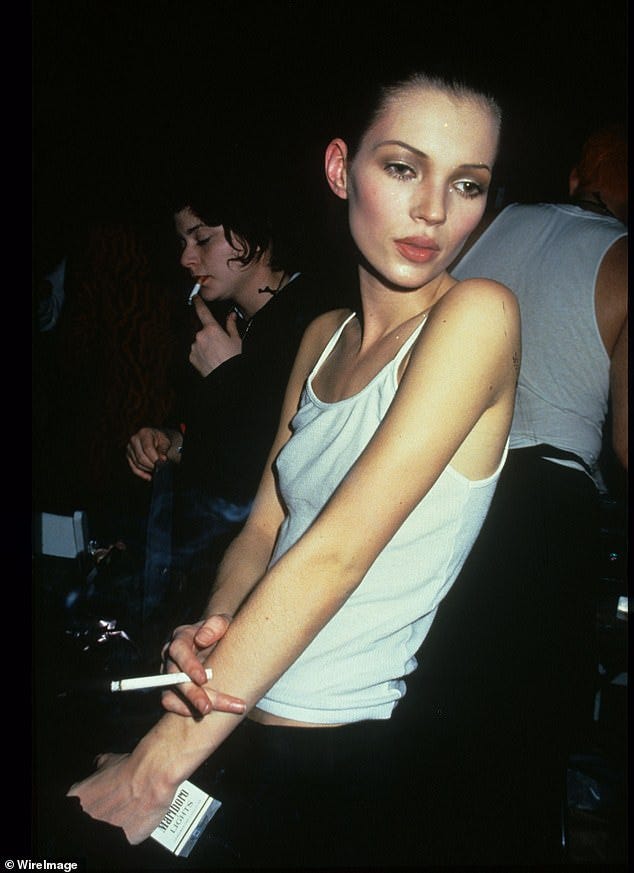

The industry’s obsession with thinness reflects deeper psychological associations that have been built into the visual language of fashion for decades. A thin body, especially when elongated and styled in minimalist silhouettes, is often coded as aspirational. Not necessarily beautiful in a traditional sense, but disciplined. In complete and enviable control. It’s cool, detached, and somehow above the messiness of real life. There’s a reason why the “heroin chic” aesthetic of the late ’90s, that starved herself and smoked uncountable cigarettes a day, has crept back into circulation even after 30-plus years—it’s become less about the actual clothes and more of what the body underneath them is allowed to represent.

But that idea of thinness as a personality trait has been ingrained not just in how models are cast, but especially in how people in the industry treat each other. It’s something I’ve seen firsthand: how weight, or the idea of being “in shape,” becomes a kind of shorthand for whether someone “fits in” or looks “cool.” It doesn’t have to be said directly for the message to land (although in a lot of cases it does, I’ve even seen fashion buyers photoshop themselves thin, and their obsession with thinness affect their buying process). And that message continues to be broadcast through campaigns, castings, and even workplace dynamics.

There was a moment, maybe five or six years ago, when it seemed like something was about to shift. Body diversity was a trending topic. Some brands started casting plus-size models in shows or e-commerce shoots. But the change didn’t quite stick. Within a season or two, the same bodies came back: mostly thin, mostly tall, mostly white. Token gestures remained, like one curvier model placed at the center of a group photo for what I heard somebody once say for “commercial balance”. But the system never really adjusted.

And there’s a reason for that, too. Thinness makes production easier. Sample sizes, which are still typically made in a US 0 or EU 34, are designed to fit one kind of model. It cuts down on fabric, simplifies fittings, and keeps the process efficient across cities and seasons. If you want to cast a body outside of that standard, you need custom samples, and that means more money, more time, and more work. Many brands simply won’t bother.

There have been exceptions. Designers like Sinéad O’Dwyer have restructured their entire workflow to accommodate different body types from the start, including offering samples from UK size 4 to 32. But this is still the exception, not the rule. Most brands continue to center their design pipeline from concept to runway around a single type of body, and the rest are asked to catch up or squeeze in.

That’s part of why thinness is so persistent to this day. We mistakenly perceive it as just an aesthetic when it’s actually commercial. And on a much deeper level, it’s cultural. For a long time, thinness has been treated as a form of cultural capital. A way of signaling taste, restraint, and status. It’s been racialized, gendered, and classed. The fashion industry may speak the language of inclusion more fluently now, but it still tends to reward bodies that conform to a very narrow definition of acceptability.

We’ve seen some efforts at regulation, mostly in Europe. France passed a law requiring models to present medical certificates proving they’re healthy and to disclose edited images. In Spain, as early as 2006, Madrid Fashion Week took a bold stance by prohibiting models with a Body Mass Index (BMI) below 18 from walking the runway. And now, with the Zara case, we’re seeing ad regulators in the UK begin to push back, calling out the way certain bodies are used to sell clothes in ways that can cause real harm. But even then, the impact is still so small. The ads are pulled, the headlines circulate for a day or two, and the next campaign looks more or less the same the next day.

The truth is, if nothing changes at the level of enforcement, we’ll keep looping through the same cycles. Performative casting. One-off gestures. Occasional outrage. And then, as per usual: silence.

Some people believe this issue has to do with representation, and while this is also true, it’s also about the psychological impact this system has on people. Fashion affects how people see themselves. Period. It shapes aspiration, identity, and even health. The pressure to look a certain way doesn’t come only from fashion shows. It comes from every ad, every feed, every post. And it reinforces a structure where only certain bodies are allowed to be visible.

And it’s not that the industry that keeps enforcing these ideals. It’s the way they’ve been repackaged, softened, and sold back to us as empowerment. Body positivity was supposed to shift the narrative, but somewhere along the line, it got co-opted by the same systems it was trying to challenge. Suddenly, magazines replaced “lose weight fast to get summer-ready” with “look healthy and strong,” which sounds better, but still pushes the same outcome: a body that needs to be fixed before it can be visible. You can be curvy as long as you still have a small waist, flat stomach, and symmetrical hips. You can be thick, but only if you’re thick in the right places. It’s still conditional acceptance, and it persists at being desirable on someone else’s terms.

Social media only amplified this. Platforms that were once places of self-expression have become stages for aesthetic surveillance. You don’t just get dressed, you need to perform style. You don’t just show your face, you filter it to match a beauty standard that keeps shifting and shrinking. Now we’re even seeing AI-generated models taking over campaigns, trained to look like the idealized versions of human bodies that already don’t exist. Just recently, Vogue came under fire for featuring AI models with hyper-smooth skin, impossibly long limbs, and not a single trace of body variation. No pores, no folds, no weight. No soul. That’s not even an attainable aesthetic anymore; it’s become algorithmic thinness and an unattainable joke. It’s the next frontier of exclusion that the industry will catalogue as “innovation”.

What’s worse is how normalized it’s becoming. These synthetic bodies aren’t even controversial anymore. They’re efficient, on-brand, and easy to control, of course. They don’t need food, rest, or rights. And that’s the direction we’re headed in: an industry where even the representation of people can be optimized, edited, and stripped of its humanity for the sake of editorial visual coherence.

So when we talk about regulating the industry, we’re not just talking about health certificates or BMI thresholds. We’re talking about setting strict, real boundaries for how beauty is built, broadcast, and consumed. Because, as much as we like to think fashion is about self-expression, too often it becomes a performance of conformity. A tightrope act where only a few bodies are allowed to stay balanced. And the rest are either asked to disappear, or shown what it takes to be seen.

But not all is lost. We’ve seen how regulation can start to move the needle when it comes to production ethics. Fashion weeks like Copenhagen require brands to submit proof of environmental responsibility before they can participate. That same kind of framework could be applied to casting and sample production—real policies, with real consequences, that protect not just the people behind the garments, but the people expected to buy into the image.

The goal isn’t to ban thinness, but to break the industry’s dependency on it as default and to ask who specifically gets erased in the process and the small percentage who benefit from it. Some of the worst forms of labor exploitation in the industry have come from brands that position themselves as luxury, Loro Piana among them, as the most recent disastrous example. If we’re willing to hold companies accountable for how they treat workers in factories, we should be just as willing to hold them accountable for how they shape the mental health of the people consuming their products.

These images go beyond editorial visuals. They’re ideals people get to consume just like food. And who gets to embody them still tells us everything about what the industry values, and what it’s willing to ignore.